Olympics for Savages: The Anthropology Days

As the 202(1) Tokyo Olympics come to a close, I thought it would be timely for us to reflect upon an all-too-often overlooked Olympic Game: the 1904 Summer Olympics hosted in St. Louis, Missouri.

The St. Louis Olympic Games in many ways was a groundbreaking one. It was the third ever modern Olympic event, and the first to ever be hosted outside of Europe.

But, it was also a complete mess.

First of all, most Olympic records prior to 1912 are questionable. There were no international standards for athletes, sporting events, and even the duration of competing. The St. Louis Olympics ran from July 1st to November 23rd, an incredible 5 months. It also seemed as if almost anyone could participate (well, if you were a white American), and the consistency in recording results was nowhere to be seen.

Second, events occurred at the height of the Russo-Japanese war which thwarted the opportunity for many European athletes to participate. Moreover, the event was hosted in St. Louis – which is in the midwest of the United States – during a time when travel was done by boat and train. So out of the 630 athletes that even had the time and money to show up, 523 of them were from the US.

Third, the standards were extremely low.

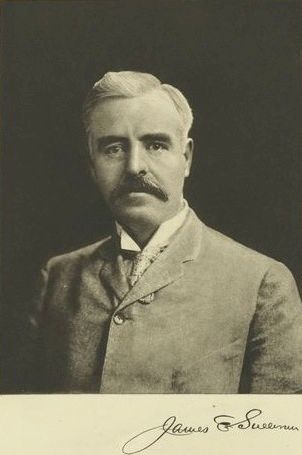

The most famous example is the 1904 marathon. This sacred event of the Olympics was tarnished on almost every front. Many of the participants were either not fully equipped to make the grueling 42 Km run, or were mid-distance runners who had no experience running such a course. To make matters worse, James E. Sullivan – the organizer of the St. Louis Olympic Games – wanted to "test the limits of the participants" and only put 2 water stations along the entire route. As a point of reference, the common number of water stations at marathons today is 16. The problems didn't end here.

There are accounts of people being chased off the course by dogs, wagons interceding in the race, and when Thomas Hicks – a tournament favorite – almost collapsed from dehydration and asked for water, the officials refused. Other runners were soon to become the first fatality of an Olympic marathon if it wasn't for the doctors driving next to them.

All for the sake of "science".

Alongside this 5 month-long event, was an even more extravagant exhibition of human behavior. It was the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (also known as the 1904 World Fair), which celebrated the 100th anniversary of the infamous Louisiana Purchase. All you history-nerds may know that the Louisiana Purchase was actually in 1803, but there were some "clerical difficulties" that pushed the event a year back.

Regardless, this exposition was massive.

Expositions were a popular event during the 19th and 20th centuries, often hosted by powerful empires or soon-to-be empires to promote their progress and power. They showcased the newest technological breakthroughs, scientific developments, and flamboyantly celebrated victories in war. But that wasn't it.

The expositions gradually shifted into a hub for entertainment and pop culture. So as the scientists, bureaucrats, and imperialists gathered to marvel at the futuristic direction of humanity, the common women and men scavenged the streets for the newest rides, foods, and entertainment.

Exposition Fun Fact: The Ferris Wheel, Eifel Tower, and the Unisphere (the world's largest globe) were all created for an exposition. Either as a form of entertainment or power-flex, but most likely both.

Out of these expositions, the 1904 Lousiana Purchase Exposition was on a new scale. It covered an incredible 1270 acres, approximately 1,000 football fields worth of land. It extended from April 30th to December 1st, a jaw-dropping 7-month exposition that attracted close to 20 million visitors.

During this long period, almost anything imaginable was sold, displayed, and studied. Brand new foods and drinks, the wireless telephone, and "primitive" human beings.

As mentioned earlier, such expositions were a place to display a nation's imperial power – which the United States was overflowing with, in 1904. The domestic assimilation efforts to detribalize Native Americans were an immense "success", and they had just annexed the Philippines after the Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars. So these "human exhibits" – hosted by the Department of Anthropology – served two purposes.

The first was to celebrate the victories in war and expansion of the American Empire. And secondly, it was to study and show the "missing links" that led to the superior white, American race.

Now, the realities of these "human exhibits" during the exposition will be introduced in detail in another article.

What I want to focus on here is the "Special Olympics" that was hosted alongside the white-washed "regular Olympics" in 1904.

In the middle of the Olympics, where untrained marathon runners were being dehydrated for the sake of "science", another sporting event was born out of the curiosity of 2 American men.

These two men are James E. Sullivan – the man who organized the Olympics and dehydrated those poor runners – and William J. McGee. McGee at that time was the president of the American Anthropological Association and headed the Department of Anthropology at the exposition.

Sullivan and McGee got together to plan what was to be called "Anthropology Days", which occurred over a two-day period in August.

The purpose of the Anthropology Days is a complex one – just like the entire exposition. But a few things are quite clear.

First, it was out of the curiosity of Sullivan and McGee. During a time when Darwin's Theory of Evolution was used to explain the inherent superiority of the white man, other dark-skinned and "primitive" people were of the highest interest. What were they capable of? Could they understand the rules? Did they have some unique powers due to living in the forests or deserts?

Second, the Olympics was dominated by whites. Many non-whites were banned from participating or did not know of the quasi-global event of the Olympics. So, Anthropology Days was thought to be a good opportunity for such people to compete.

However, finding that convincing those people who were locked up inside an exhibit for 4 months to participate in a "sporting event" challenging, Sullivan and McGee began to offer incentives. Such incentives ranged from watermelons, flags of the U.S, to monetary prizes for winning. In the end, approximately 100 men (no women) from diverse groups such as the "Patagonians", Pygmies, Chippewas, and Ainu participated. (Source: St. Louis Public Library, Universal Exposition N.P Vol. 12:137, St. Louis Republic, 1994)

What's notable in this recruitment process was the Sullivan and McGee did not limit themselves to people who were being displayed as "savages". The two men went to non-white nations who were emerging as industrial powers to participate as well. This included the Japanese, Chinese, Indians, and Sri Lankan people who were attending the exposition for the same reason as the British or the French: They were here to show the world their developing power.

As expected, they all strongly declined.

So between August 12th and the 13th, these 100 men from diverse tribes and nations participated in the make-shift Olympics called "Anthropology Days". The events were wide and varied. From running events, archery, "baseball-throwing", pole climbing, and even tug-of-war, the participants competed in front of a crowd of 10,000.

Yet the results – at least from the American point of view – were disappointing.

The participants were either unaware of certain rules or were entirely disinterested in competing at all. McGee was unable to gather data of the "primitive" people's behavior and actions to further the study of Anthropology. And yet, the winners were paid off with the various incentives that were promised.

Although it was unambiguously clear that the failure of the event was due to cultural differences and the lack of practice these men had, Sullivan continued to assert that these people were inferior to the "white Americans".

It becomes evident that Sullivan and McGee understood this fundamental flaw in their comparison between whites and "savages", as they planned another event called the "Anthropology Meet".

This new event was planned to take place in September, giving Sullivan a few weeks to prepare. He hired trainers and provided the participants – who were mostly Phillipene natives – professional training. However, curiously enough, there are not many records to illustrate the event itself and the outcome. But knowing Sullivan's extravagance and publicity, it most likely was another failure.

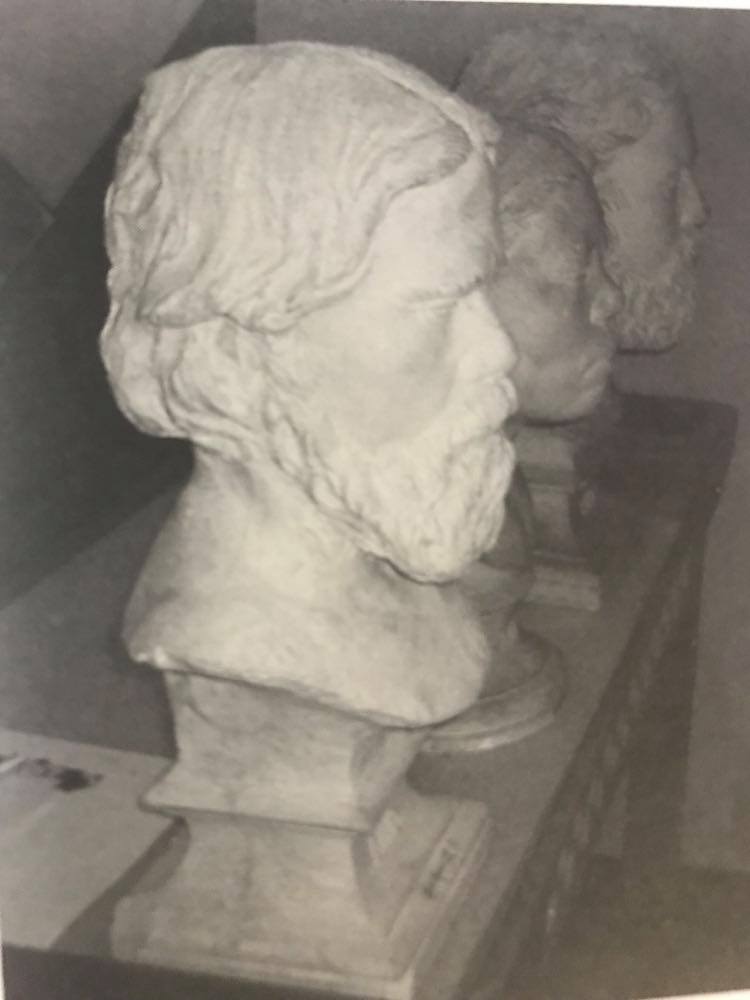

Now to conclude, what is important to note is that as unfortunate and inhumane such expositions and human displays may seem today, they have inadvertently provided many descendants of these tribes and people groups resources to remember their past. Through photos, archival records, books, and even statues – they have become important pieces of the past that allow us to reconstruct their stories.

An Ainu descendent – whose grandparents were a part of the exposition – is recorded to have said this in response to an image of her grandfather made during the Louisiana Purchase Exposition:

Seeing the image of a much younger version of him seemed like he was talking to me, saying, "Hey! It's been a while!" The detailed and high quality of his image tempted me to respond, "Yea grandpa, I'm here to see you" (Miyatake, 2010:4).

The countless disturbing and complex pasts of our civilization should not be simply deemed evil.

Yes, the many tribal people were put on display and labeled "savages" and "inferior", but within the incredible power system of such international expositions and sporting events – they asserted their agency. They chased off rude photographers, educated the myopic public about their customs, adapted to new situations, negotiated financial and economic relations, and more.

Moreover, they left their mark on our past. It is now up to us; to either leave them in the past, or bring those memories with us into the future.

![[Guest Post] Exploring Colonial History through Art](/content/images/size/w750/2023/11/graphite-island-banner.png)

![[Guest Article] On Grossman: How a Pseudoscientist Pushed Our Understanding of Killing Back 20 Years](/content/images/size/w750/2022/09/256297-1330622535.jpeg)