The Story We Tell: Collective Memory, History, and Identity

Inside a conference room at a luxurious villa, a group of 15 men gather around a table. The building overlooks a gorgeous body of water and a neatly organized garden full of green.

Since the building was constructed in 1914, it served multiple purposes. It housed extremely wealthy businessmen, frauds, and at one point acted as a school.

But on this particular day, it served as the location for one of the most exclusive and high-profile meetings for the nation's first class.

Among the men in attendance, more than half of them held Ph.D.'s from elite universities, and the others were top-ranking officials of the nations. For months, these men have been searching for a solution to one dire question.

"What are we going to do with the Jews?"

This meeting is now remembered as the Wannsee Conference, which took place on January 20th, 1942. The villa is located southwest of Berlin, and is known as the crucial turning point in the development of the "Final Solution".

This Final Solution (Endlösung) gave birth to what we referred to as the Holocaust.

The House of the Wannsee Conference (Haus der Wannsee-Konferenz) is now a memorial museum, dedicated to the systemic extermination of the Jewish people that was planned in the very building.

It is engraved into the pillars of the structure to maintain the memories and history of this tragic past, to remind those who visit what had happened not so long ago.

However, turning this house into a memorial was quite controversial within the city of Berlin.

This article is about how we collectively remember, its relationship to history, and why the way we imagine the past is consequential today.

After the fall of the 3rd Reich, the house was left to stand on its own. It was just another building on the southwest edge of Berlin.

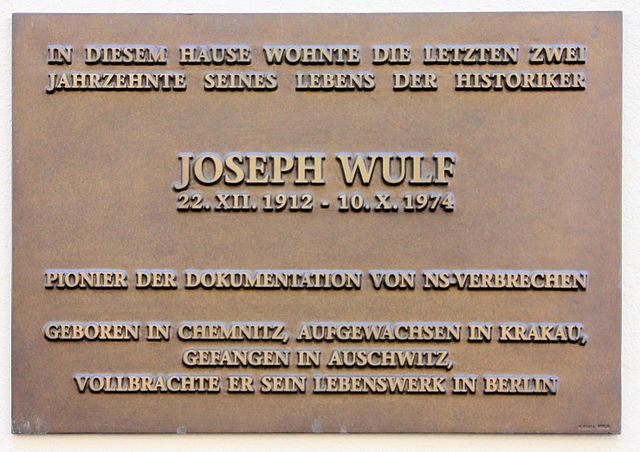

Things began to change in 1965. When a Jewish historian named Joseph Wulf, proposed that the building be made into a memorial and research center. Wulf himself was an Auschwitz survivor, who dedicated his life to documenting and spreading the realities of the Holocaust. Yet, the West German government didn't (or couldn't, depending on how you look at it) do much.

The reason being that the building was used as a school, funding was not available, and the topic of the Holocaust was a strongly contested one.

Wulf's suggestion further polarized the already split nation (the nation was literally split into two, West and East Germany). People went back and forth on the streets, on the press, and even between politicians on what to do with the house.

But the opposition's stance may not be what you think. The main argument against the house becoming a memorial was:

"Why that house?"

It was a beautiful villa that housed students on school trips and camps for years before and after the war. Surely, it was full of nostalgic memories of those children, rather than that one meeting!

The debate seemed to go on forever. Was it a beautiful house where children played hide-and-seek? Or was it a place oozing with the horrors of the 2nd World War?

Joseph Wulf, unable to see the incompetence of the government and his wishes not actualizing, committed suicide in 1974. Before he jumped out of his apartment window, he left a note to his son:

"I have published 18 books about the Third Reich and they have had no effect. You can document everything to death for the Germans.... Yet the mass murderers walk around free, live in their little houses, and grow flowers" (Browning, 2004)

Even after Wulf's death, the debate continued for more than a decade.

Finally, in 1987, the decision was made to make the building into a memorial. And 5 years later – on the 50th anniversary of the Wannsee Conference – the museum opened to the public.

To this day, the House of the Wannsee Conference is a place where people go to collectively remember the horrors that were birthed from that one meeting on January 20th, 1942.

What I described above is an interesting story about one of the most recognized historic events in the world. Yet it also describes the process called "collective remembering".

Collective remembering is the process in which certain members of society decide how to construct the narrative of their past. This process is almost always an identity project, where ideas of "who we are" become solidified.

Once this solidifies – like when the memorial was built in Wannsee – it becomes collective memory. The narrative of collective memory is best described as an autobiography for a certain group. Such processes are crucial for social cohesion at all levels; from friendships, families, to nations.

This autobiographical narrative of the past – like "we the people" or "our nation" – allow people to share the same "history" (I put this in quotations because I need to distinguish between the generic use of the word and the discipline). My favorite description of this comes from a footnote in a book by Alessandra Tanesini, a philosopher at the University of Cardiff. She says:

Collective memories are generative of content since they enable individuals to have quasi-autobiographical memories of events which they did not personally experience (Tanesini, 2018:206).

What I love is her use of the word "quasi-autobiographical". Quasi- means seemingly or partly. So through the construction of these collective memories, individuals within a society are able to relate – only partly – to past events they may not have been experienced.

This is seen in the German chancellor Angela Merkel's speech in 2019 when she visited the Auschwitz concentration camp.

She starts her speech by saying:

"I am filled with deep shame, in the face of the barbaric crimes committed here by Germans" (Merkel, 2019)

Chancellor Merkel was born in 1954, 9 years after the Nazi state dissolved. How can someone be filled with shame about something she personally did not experience?

It's because, through the processes of building memorials and admitting to the crimes of the past, the German society has built a collective memory that allows for such "quasi-autobiographical memories". The shame of the years of systematic persecution of the Jewish people is ingrained in their identity.

In other words, through the construction of collective memory, part of being a German citizen was to face the past of the Holocaust. And when this narrative of the past is challenged, it receives a lot of pushback.

This brings us to the point where the tension between collective memory and the discipline of history becomes important.

History aspires for an objective account of the past, regardless of the consequences for identity. It recognizes the fluidity and complexity of the past and "...can change in response to new information" (Wertsch and Roediger, 2008:321).

On the other hand, collective memory is looking to build a narrative about a group's past. It's direly impatient with ambiguity and is often resistant to change.

Let's look at the relationship between collective memory and history by looking at two examples.

The first example is the already familiar story about the House of the Wannsee Conference. Initially, after the war, the narrative of collective memory was a positive one. It was full of memories of school trips and getaways for the busy German public. Yet, such memories contested with the history of the Holocaust – and that one meeting.

So through years of disputes, it was finally settled that the site be made into a memorial. But again, this change in the narrative of collective memory is contested with the history of that very building!

It was equally true that the building was used as a site to plan one of the worst atrocities of our species, as well as a loved villa with a beautiful view. In such ways, collective memory simplifies, distorts, and ignores parts of the past to create a certain story.

The second example may be more familiar to most of my readers.

In 2002, a shocking announcement was made public: George Washington – the first president of the United States – owned 9 slaves at his house just 1 block away from Independence Hall in Philadelphia, PA.

Saying that Independence Hall is foundational to the United States is an extreme understatement. This is the very place that the founding fathers of the nation signed the Declaration of Independence, giving birth to the nation of freedom and democracy. It is even a UNESCO World Heritage site, due to its recognized impact for spreading such ideals across the globe.

So people were angry. People were angry that such a history was buried and unknown.

Historians, NGOs, and community groups rallied together in a matter of months, calling the National Park Service to recognize this history and properly commemorate the people who were held as slaves at the site.

So on March 26th, a resolution passed that a plaque would be hung at the slave quarters.

Yes, a plaque.

Oh man, you can imagine how furious people would have been hearing this news! I mean your blood may be boiling just reading about this right now!

Soon after, an online petition began receiving thousands of signatures, and historians further argued against this resolution.

In response, the Superintendent of the Independence National Historic Park –where Independence Hall and other sites symbolizing American freedom are located – wrote a letter.

The Superintendent at this time was Martha Aikens, an African-American woman who had a successful career in the National Parks Service. Unfortunately, her response made things much worse.

She wrote a letter in response to the growing calls for a proper and full-fledged memorial to be erect at Independence Hall. In the letter, she said they can't do any more than a plaque, and I quote:

"Because we genuinely believe that it would be confusing rather than revelatory" (Aikens, 2002)

Basically, she is saying that people would be confused to come to a historic site of liberty and be faced with a memorial for slaves!

This deepened the anger of the people. More and more signatures were added to the petition and even marches were organized to fight for something more than a plaque.

There's much more to the story, and if you want to read more click here.

To wrap up – as this article is getting quite lengthy – it took 8 more years of bureaucratic jargon to make a proper memorial and recognize this forgotten history.

The story I just illustrated was a case where the study of History altered the collective memory of the United States. New information about the past altered the narrative of the American public.

Yet as you may understand, that is not always the case. Collective memory need not be accurate, it just needs to be precise. As long as the greater majority of the people within a given group or nation adheres to the narrative, a new social identity and cohesion can be achieved.

To end, how we tell the story of our past is important because it tells us who we are.

Even more consequential, is that our collective memory tells us who we are not.

![[Guest Post] Exploring Colonial History through Art](/content/images/size/w750/2023/11/graphite-island-banner.png)