[Guest Article] On Grossman: How a Pseudoscientist Pushed Our Understanding of Killing Back 20 Years

![[Guest Article] On Grossman: How a Pseudoscientist Pushed Our Understanding of Killing Back 20 Years](/content/images/size/w960/2022/09/256297-1330622535.jpeg)

About the author: Seth Allard is a USMC Veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom, deploying as an infantryman in 2005 and 2008 to Al Anbar Province, Iraq. He holds degrees in history and cultural anthropology, has over 13 years of experience in the field of mental health and health research, and is published on the topics of suicide in Native American and Military/Veteran communities. Seth is currently a Ph.D. student in the Social Work and Anthropology dual doctoral program at Wayne State University, Deans Diversity Scholar, and was recently selected for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Research Scholars program. His current focus is interdisciplinary and collaborative approaches to mental health and suicide in the US Marine Corps. He lives with his Wife, Son, and Dog in Southeastern Michigan. Contact: sallard@wayne.edu

Dedication

This article is dedicated to the memory of Ian Fishback, a former US Army Major, West Point Professor, and activist for peace who tragically passed away in November 19th, 2021. Ian's work, life and vision stand as a lasting example of ethics to our nation, and specifically, as a model of scholarly rigor and intellectual passion for service members and veterans seeking a fuller understanding of war, violence, and ethics. Ian, Chi Miigwetch (Thank You Very Much).

Introduction

We are flooded with a nonstop stream of violent and deadly events in the United States – Captions reading “police,” “mass shooter,” “mental health,” “use of force,” “school shooting,” “race,” “[insert number of] people dead” jump off the screen with predictable regularity. Writing about violence in America has become the daunting task of pivoting from tragedy to tragedy, resulting in more questions than answers, and far more divisiveness than unification in stemming violent deaths. Watching my own community respond to the killings in neighboring Oxford, Michigan, and our own school district scramble to review safety protocols and procedures, make the issues more personal and immediate. There have been over 61 school shootings since I began pursuing this article in early 2021, and like many parents, dropping off my child at school each morning has morphed into a sick version of Russian Roulette. A spectrum of violent behaviors persist in our society, from mass shootings to police deadly use of force cases, each backgrounded by changing patterns in violent crime, macro-level issues, politics, and the ever-present ‘culture wars’ over policing and violence. Our inability to agree on working solutions to violence highlights the urgent need to discuss and parse helpful approaches to violence from the divisive and popular narratives and theories embedded in media coverage and public discussion. We must identify key figures and groups who feed and participate in a toxic cycle of unhealthy approaches towards violence and prevention, which divert resources and attention and ultimately contribute to counterproductive, even harmful approaches to reducing violent deaths.

In this article, we spotlight the “Killologist” Dave Grossman, a former Army lieutenant colonel who bills himself, and is seen by many within military, law enforcement, and security circles, as parts genius, scholar, soldier, scientist, historian, and altruistic hero of “Sheepdog” culture. Through his “Killology” based books, seminars, and media appearances, Grossman looms large over the rising questions about police behavior in America, having an outsized impact on the way many law enforcement officers view themselves and their behavior in the field, as well as our military's common understanding of killing and trauma. In reality, Grossman is a clever fraud and pseudoscientist whose theories about the factors involved in killing, in which he grounds his advocacy for the sheepdog mentality, lack the academic merit they should have. All the while, Grossman’s ego and pocketbook, as well as his acolytes’, have grown fat on violence, fearmongering, and an impressive ability to manipulate inflammatory narratives of ‘good and evil’ and inject destructive ideological views within military and policing culture.

Last spring, I learned that Grossman’s Bullet Proof Mind seminar in Ann Arbor had been canceled due to the fallout over a resurfaced video, where he enthusiastically stated that killing a person leads to the “best sex,” and that “both partners are very invested in some very intense sex.” “There’s not a lot of perks that come with the job,” he tells a room of police officers, “You find one, sit back and enjoy it.” Grossman and his supporters claim the video was subtly edited to remove context, though Grossman makes the same claim nearly verbatim in a 2015 recording of the training of the Bulletproof Mind seminar at Cannon Airforce Base.

Once a longtime trainer of U.S. military personnel and law enforcement, Grossman’s career has since suffered amid coverage of controversial and unsupportable statements and his being described as a pivotal figure behind the militarization of police. Professionals familiar with Grossman responded by saying “is he still being hired for trainings?” “Is anyone hiring him anymore?” And “I’d think no one would hire him.” Such statements reflect a pattern of military, security, police, and professional organizations disassociating from Grossman’s content and canceling training since media coverage of his propagation of “warrior” style policing revealed that Grossman’s views do not align with best practices, standards, and ethics. With the police use-of-force circuit a less viable means of income, Grossman is largely limited to church safety seminars, his online courses through Grossman Academy, and guest appearances and commentating. The Killology Research Group confirmed that Grossman’s training calendar was removed from his business website out of safety and security concerns, though avoiding protests and further cancellations is another plausible explanation.

Still, Grossman’s writings, theories, qualifications, “research,” and views strongly reverberate across generations of military, law enforcement, and would-be-warrior-scholars. His career and identity are monuments to a popular and caustic interpretation of Judeo-Christian philosophy on war and killing that states that it’s okay to kill, so long as you kill the right people, and you respond to death, trauma, and use of righteous violence with an attitude of equally righteous indifference. The “Sheepdog” analogy of the protector standing between the wolf and the sheep, specifically, has taken on a life of its own and become deeply embedded within police and military culture. Most combat arms veterans can recall platoon-mates spouting the tenants of “Killology,” a term which one professor from a major university confessed, “I just can’t take seriously.” Just how serious, then, is Grossman taken by social scientists in general?

Regarding their opinion of Grossman’s work and the term “killology,” multiple academics and professionals contacted by the author and those who specialize in areas in which Grossman claims to be a “world renowned expert” and leading authority – such as PTSD, positive psychology, crisis counseling (during and after mass shootings), or criminology - responded that the neither Grossman nor Killology “rings any bells.” One person who is actually cited in On Killing responded, “Who is Dave Grossman?” Others reacted with mixed reviews of Grossman’s work. Robert Meagher, professor emeritus at Hampshire College and author of Killing from the Inside Out: Moral Injury and Just War, stated:

In simple terms I think his book ‘On Killing’ made an important contribution to the understanding of modern war and its impact on those who wage it and those who suffer it. I find…On Combat to be much more complicated in its impact. That book and his work with police forces in the country have, I feel, contributed to the militarization and excessive violence of some police forces. Seeing and arming them as warriors is very problematic. He explained in On Killing how our armed forces have become exponentially more lethal in recent decades. Applying that same training to police has had, in my view, dire consequences. On the other hand, I see his campaign against violent video games for children and young people in Assassination Generation as positive and helpful.

The fact that Grossman brings to light a larger discussion of psychological and social contexts of violence, highlights the impact of media on children, and advocates for support for veterans and police, are things even his critics have given him credit for. However, specific conclusions he has drawn in his books and seminars, such as the claim that humans are innately programmed to avoid killing at almost any cost, or pointing to violent video games as the direct cause of gun violence, continue a theme of reductionist and simplistic claims designed to complement specific historical and cultural narratives, and therefore should be questioned. Regarding the role of violent video games, a central topic of political and academic back and forth, a 2015 analysis of the scientific literature on violent video games by the American Psychological Association found that: “Although additional outcomes such as criminal violence, delinquency, and physiological and neurological changes appear in the literature, we did not find enough evidence of sufficient utility to evaluate whether these outcomes are affected by violent video game use.” This study also points out that a lack of research has been conducted on significant risk factors, such as socioeconomic status, on violence and aggression. A recent 2021 study by a professor of economics at the City University of London Agne Suziedelyte further weakens the position that violent video games are a direct cause of violent, criminal behavior, a case that Grossman consistently makes in his descriptions of a “virus of violence.”

As one expert on criminal justice and policing, Kalfani Ture, a former police officer who is now a professor at Mount Saint Mary’s University in the department of sociology, criminal justice, and human services, bluntly summarized: “Grossman? That dude says some crazy shit.” Ture further points out that “the uptick in community violence, homicides, guns, as well as police death in the line of duty will bolster warrior style policing. And there are millions available for this training - funding made available from COVID response and Biden’s infrastructure plan.”

The scientific literature and insights of social scientists with experience in applying rigorous research to pressing public issues reveal the danger of teaching law enforcement and military members, as well as leaders and policymakers, that widespread violence is reducible to simple, and often highly politicized, cause and effect scenarios and explanations. As a direct result, leaders, policymakers, and communities may fail to recognize or target systemic factors and issues that we see play out on the ground during mass killings.

I was deeply intrigued by the events unfolding around the resurfaced video, partly from my familiarity with Grossman’s popularity as a Marine infantry veteran, and initial responses I received from individuals cited in Grossman’s work and coverage surrounding Grossman’s activities and impact. I resolved to closely read On Killing and several other works by Grossman, poured over podcasts, videos, and profile pieces, contacted individuals familiar with his work or cited in On Killing, and experts working in areas discussed by Grossman. What started with curiosity morphed into a chilling realization that Dave Grossman, the most popular source of information on combat and killing in the military and policing communities since the late 1990s, single-handedly pushed our understanding of death, killing, and combat back years. The impact on our law enforcement’s ability to serve communities in times of crisis and high stress, and military servicemembers' ability to gain healthy understandings of combat stress, took place in the interest of pushing political and ideological discourse and a set of cultural beliefs around the appropriateness of killing and violence, all founded on false evidence and misleading qualifications.

Who is Dave Grossman?

Grossman’s biography has been widely covered on various platforms, from podcasts and profile pieces to his own writings, presentations, websites, endorsements and book forwards, and his 70-plus page CV. Touting personal accomplishments, qualifications, and honorifics is a major theme in his writings, public appearances, and seminars. “People know me. They trust me,” “one of the world's leading authorities,” and “internationally recognized scholar” are mantras on and off the stage and etched deeply within promotional and course materials. Such self-aggrandizement contributes to his celebrity status in military, police, and security circles, to whom Grossman represents all things combat and killing – a modern Clausewitz (On Killing = On War). As Thomas Aveni, a well-known national police use of force trainer Thomas Aveni, who debated Grossman in-depth on his erroneous interpretation of police use of force and gun violence data explained to the author, Grossman has “a cult following.”

A retired Army lieutenant colonel, Grossman served in the interwar years between the Vietnam and Iraq-Afghanistan Wars, taught psychology at West Point, and finished his military career directing the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program at Arkansas State University. At ASU, Grossman published his breakout book On Killing, followed by On Combat and similarly themed books, articles, essays, forewards, chapters, entries, op-eds, podcasts, and even children’s books, poetry, and Christmas carols. Grossman’s works are usually co-authored with self-proclaimed martial arts, personal defense, and tactical-security gurus like Loren Christenson and Bruce Siddle. Like many with mixed policing, military, or martial arts backgrounds, Grossman has capitalized on a post-9/11 and anti-terrorism market, or what has recently been described as a “warrior-cop industry” or cottage industry that caters to would-be “good men with guns”. On Killing launched Grossman’s career as a writer, paid speaker, and self-styled expert on all things killing for over 20 years, solidifying his position as the ‘go-to’ source of information and an integral voice when it came to police, military, and security culture. It didn’t hurt that, as one well-known writer (speaking on condition of anonymity) consistently cited in On Killing deduced, “It looks like Grossman found his ringer.” Grossman’s work is entrenched in the simplistic and false claim that humans are innately resistant to kill, the implications of which are explained through the “Sheepdog” metaphor. Grossman states in On Killing that most people are sheep, peaceful creatures incapable of violence,

…[living] in denial; that is what makes them sheep. They do not want to believe that there is evil in the world. They can accept the fact that fires can happen, which is why they want fire extinguishers, fire sprinklers, fire alarms and fire exits throughout their kids’ schools. But many of them are outraged at the idea of putting an armed police officer in their kid’s school. Our children are dozens of times more likely to be killed and thousands of times more likely to be seriously injured, by school violence than by school fires,but the sheep’s only response to the possibility of violence is denial. The idea of someone coming to kill or harm their children is just too hard, so they choose the path of denial.

“Wolves,” by contrast, are “aggressive sociopaths” genetically and behaviorally primed for violence, who lack empathy, and are predisposed to mercilessly feed on the sheep. As you may guess, “Sheepdogs” possess a combination of empathy and the ability to use “righteous violence,” defending the sheep “when the wolf knocks at the door.” Extreme or widespread violence results from the absence or subjugation of Sheepdogs within society by sheep themselves, who are unable to defend against the manipulative power of figures, groups, or social influences.

Grossman projects a “dark vision” for America’s future by playing up this apocryphal call to arms, consequentially solidifying the need for “Sheepdogs” and their authoritative role within society. Ironically, American slavery, Native American genocide, and under-reported mass killings of African Americans during the Jim Crow era are not mentioned in his ‘analysis,’ most likely because these events run counter to the theme of American exceptionalism and the imagery of Sheepdogs within policing and military circles. Nor does he address the irrefutably criminal treatment of civilians by police, such as the murder of Philando Castile by Jeronimo Janez, who attended a training directly modeled after Grossman’s Bulletproof Mind seminar. While Grossman developed the course, other organizations, companies, and instructors offer and financially profit from teaching the fear-based curriculum attended by Janez. A Men’s Journal article captures Grossman’s attitude towards police accountability for illegal use of deadly force. Referring to the strangling and death of Eric Garner in New York City, who pleaded for help, Grossman simply stated “if you can talk, you can breathe.” Of course, the scientific and medical evidence seen by millions during the trial of Derek Chauvin proves otherwise. Grossman attributes criminal police activity, mental health problems, and suicide within police and military ranks to, among other factors, immaturity and lack of sleep, and the psychological harm that results from failing to understand that “killing is just not that big a deal.”

Grossman’s views stem from “Killology”, a field of study invented to address what he felt was a lack of research regarding the psychological and physiological process of killing, or what he described in On Killing as:

The scholarly study of the destructive act, just as sexology is the scholarly study of the procreative act. Killology focuses on the reactions of healthy people in killing circumstances (such as police and military in combat) and the factors that enable and restrain killing in these situations.

What Are(n’t) His Qualifications? Gaining the Authority to Give Authority.

His authority to create “killology” rests on what he describes as a “menage a trois of soldier, scientist, and historian,” according to the book. Yet, Grossman’s wielding of these titles is misleading. While his shingle reads “Killology Research Group,” (website recently renamed “Grossman On Truth”) there seems to be no evidence that Grossman participates in research like, for instance, that conducted by major universities, policy and healthcare institutions, or clinical researchers. Instead, Grossman presents information based on reviews of blogs and media, makes overgeneralized interpretations of public reports and data on violence and crime, and consistently rehashes figures and conclusions from outdated and conflicted sources. While Grossman’s writings and presentations cite established works and authors, and information on topics related to psychology and sports science such as parasympathetic response (or fight, flight, freeze), much of his work is constructed of textbook-level information and presented to and received by audiences as knowledge that originates with Grossman (for example, Cooper’s Colors described as “Grossman’s [sic] 5 conditions of physiologic readiness”).

Grossman’s claims of being a psychologist are correct in only the most basic sense. The masters in counseling psychology program he completed, comparable to the current University of Texas education counseling program, exposed him to psychological theory and practice. However, such programs primarily train students “to work as teachers, counselors, evaluators, and researchers in educational environments.” In other words, Grossman was trained to be a school counselor, not a clinical psychologist or researcher, and his ‘clinical’ experience is limited to a middle school counselor internship. Of course, this criticism is not intended to downplay the worth of school counselors, especially in today’s climate, or insinuate that without a Ph.D. you cannot study human behavior.

But Grossman taught psychology at West Point, right? Right. Grossman was selected to teach psychology at West Point without possessing a graduate degree or experience in his field, which is a common practice for selecting officers to serve as instructors. This pathway for gaining a teaching position goes against the grain for hiring standards at most major universities, where a combination of a master's or Ph.D., years of experience in teaching and research, and peer-reviewed publications are common requirements.

Most ironic, however, is that Grossman has never experienced combat, which is somehow spun into an additional qualification – his distance from combat equips him with the objectivity necessary to prevent bias in studying trauma and violence. The constant use of ‘Army Ranger’ is also deceptive. While Grossman completed Ranger training — the Army’s “premier leadership school,” he never served in the service’s elite Ranger Regiment. Soldiers who complete the training, yet do not serve in the capacity of an Army Ranger usually forego claiming the title to avoid misrepresenting themselves as elite soldiers. In his bio, he consistently references the military schools and war colleges he attended in order to keep advancing in rank. Grossman’s military career, while accomplished, is otherwise unexceptional.

These points may seem like minor quibbles, however, aiming a powerful set of self-inflated qualifications toward unsuspecting and often eager audiences have furnished Grossman with incredible influence and standing, despite lacking scholarly, clinical, or special military experience. On the flip side, many police officers, security professionals, and service members, from enlisted to officer, swallow On Killing tail and all, without acknowledging or critically assessing the absence of any rigorous scholarship. Again, the interplay between Grossman’s presentation of theories on killing and mass violence and receptive audiences underscores the overpowering presence of cultural and political discourse, which exists in both Grossman’s works and words, and the spheres in which he operates.

A Deeper Dive into On Killing: The Book Review That Never Happened

Grossman’s expert opinions are veiled attempts to impart a personal, religious, and cultural perspective on what he calls ‘killing behavior,’ which is easy to understand when discussing On Killing, a book revered as gospel by many people in military and law enforcement and used as boilerplate for Grossman’s later writings and seminars. Initial reviews fell between praise and skepticism with respect to sources, data, and supporting logic. Kirkus Reviews found that “some perceptive, original ideas can be dredged up by this awkwardly written, haphazardly annotated treatise on the psychological forces that come into play in killing on the battlefield.” Foreign Affairs, meanwhile, said that while Grossman “…writes well and persuasively… Historians…will stir uneasily as they examine his footnotes, which cite sources from Soldier of Fortune Magazine to the surveys of S. L. A. Marshall to various popular works of history.” Unfortunately, reviews failed to notice the red flags throughout Grossman’s ‘research,’ which were more expertly uncovered by military historian Robert Engen’s critical review.

Cover to cover, On Killing is a compendium of biased analyses of criminal statistics, surface-level descriptions of physical responses to trauma and behavioral conditioning, retrospective diagnoses (diagnosing historical figures or groups using modern diagnostic criteria), and erroneous interpretations and use of historical and literary sources on war and violence (e.g., is the Bible a reliable source of empirical data on psychological reactions to combat and trauma?). Grossman leans heavily on outdated Freudian principles, such as “Eros” and “Thanatos” (which is akin to designing a modern car from a replica Model-T), cherry-picks passages from otherwise valuable sources, stuffs the pages with overly lengthy excerpts, improperly cites psychological studies, and uses Soldier of Fortune Magazine as a primary source. A primary source is a document that provides a verifiable first-hand record of events, often dating to the time of the event. Professional historians use a variety of primary sources, ranging from diaries, letters, reports, photos, maps, surveys, receipts, and physical artifacts, to present a cohesive picture of human history. A highly controversial piece of popular culture, SoF unabashedly pushed a post-Vietnam “apocalyptic” or “millennialism” narrative (with extreme prejudice), creating a space for what was described as disaffected veterans and would-be warriors alike through fantastical storytelling, and at times, daring war correspondence. The purpose of the magazine was to provide politico-tainment, and the magazine’s apparent trust in the voracity of each contributor’s story (was every hair-raising article filled with blood and gore written by a combatant or veteran? Accurate or unembellished?) would prevent any professional researcher from approaching SoF as a de facto representation of veterans’ psychological and social experiences on the battlefield.

Controversial Sources and Findings.

In addition to relying on SoF as a reliable source of information, Grossman builds his entire thesis, including the “Sheepdog” analogy, on the controversial findings of S.L.A. Marshall. S.L.A. Marshall was a “newspaper man” tapped to conduct research on American soldiers’ reactions in combat, culminating in multiple book, most famously Men Against Fire (1947). Marshall’s methods and “data” have been called into question numerous times (SLA Marshall and the Ration of Fire, SLA Marshall’s Men Against Fire: New Evidence Regarding Fire Ratios). While Men Against Fire can serve as a case study of ‘dos and don’ts’ of early military research, blanket reliance on Marshall’s conclusions does nothing to push the bounds of military science and opens the door to drastic misinterpretations of behavior in combat and the value of behavioral science in understanding violence. According to Engen, a:

…flawed understanding of how and why soldiers can kill is no more helpful to the study of military history than it is to practitioners of the military profession. More research in this area is required, and On Killing and On Combatshould be treated as the starting points, rather than the culmination, of this process…I am not an expert in biology or psychology, but even a layman’s reading of the literature turns up credible works that clash with Grossman’s interpretations. And in terms of military history, Grossman’s over-reliance uponS.L.A. Marshall’s famous “ratio of fire” data represents a serious shortcoming.

An unaddressed shortcoming of Grossman’s research, writing, and seminars is a complete lack of evidence supporting his claim of conducting interviews for On Killing. No questions, analysis, or excerpts from interview transcripts are provided, unless an extremely small number of reconstructed and frequently referenced personal stories of conversations with veterans counts. Grossman’s own timeline for research is also contradictory. At the beginning of On Killing, he describes a five-year research period, and at the end, reveals that the research took place over 20 years. Did Grossman’s “research” begin before he qualified as a soldier and scientist? Were his “data” simply recollections of personal memories? Did he simply and flippantly approach and ask veterans “What was it like to kill?” – a sick question many veterans are often subjected too.

Failure to Follow Ethical Research Practices.

Another issue absent in other critiques is Grossman’s apparent failure to follow ethical research practices required of such work, which he displays some awareness of in mentioning the Nuremberg Code, which is extremely troubling given that On Killing centers on experiences with violence, death, and discussion of these sensitive topics with traumatized individuals, with the goal of furthering a scientific understanding of behavior. When researchers encounter personally identifiable information (names, addresses, health information) or gather information on sensitive personal experiences, they must submit a research protocol to a university or organization Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (IRB), which reviews, approves, or denies a research protocol. This process provides an ethical check on research by ensuring confidentiality and protection for research participants (interviewees).

Research ethics is more than dotting I’s and crossing T’s. Sitting with a person and asking about sensitive topics requires significant consideration for their safety and wellbeing (providing counseling resources, training to handle mental health crises, knowing when to stop an interview). The extent of Grossman’s ethical considerations are outlined in the book as follows: “All those who spoke with me have been promised anonymity in return for their secret thoughts.” My own IRB protocol for suicide research, in comparison, was nearly 40 pages, passed two review boards composed of community leaders and social scientists, and involved collaboration with mental health professionals to ensure safety for participants. This may seem restrictive, but no soldier would go on a mission without a well-developed and reviewed operations order. Likewise, no researcher would dredge up memories of war without a vetted protocol to ensure safety and confidentiality; a protocol apparently absent in Grossman’s work.

While Grossman addresses interesting lines of thought, his work is also not based in originality or a critical reading of the literature, which is made obvious given his constant use of broad and unsupported generalizations. The focus on space and “distance” in multiple sections of On Killing, for instance, excludes Hall’s theory of Proxemics, developed in the 1950s and 1960s and considered a key contribution to studies of society and “space.” The Marine Corps Combat Hunter program took advantage of Hall’s work by taking advantage of the concept of proxemics to account for space and distance when calculating danger and risk. “Killology” completely sidesteps the field of “Thanatology,” pioneered in 1903 with a focus on death and dying. Undercutting Grossman's preposterous claim that no one has systematically studied the psychological processes of combat is the voluminous work of John Boyd, who Grossman fails to cite and is known to many readers familiar with the “OODA Loop.” Boyd was a gifted, yet humble scholar from whom we continue to learn critical lessons on cognitive processes of combat.

Seeking historical figures and works — which Grossman states he has done — reveals uncited historical writings, such as Musashi’s Book of Five Rings and Dokkodo. Musashi, a renowned Samurai, philosopher, and artist expounded on mental, social, and spiritual reactions to combat and warrior identity. Such fields, works, and theories were available for critical study before, during, and after Grossman’s research for On Killing. The dearth of critical reading and reliance on limited sources and use of excerpts to support Grossman’s personal assumptions is analogous to shooting a bow and painting a bullseye around the arrow.

Who Let the Sheepdog In? Exploring Early Reviews and Involvement of Academia

Efforts to clarify these points with Grossman and gain a copy or further description of his research protocol, which a professional social scientist would be able to provide, went unanswered. Grossman’s literary agent Richard Curtis, in response to the questions, “Would publishers or writers who appeal to wider audiences [as Grossman did] normally provide a review or some form of stamp of approval for how the research was conducted? Or is that a responsibility that lies with the author?” stated that “Authors of academic books or scholarly nonfiction books for commercial publishers are required to have their work vetted by other academics. And I know that anyone using official government documents must get clearance from the Pentagon. But I believe Dave's scholarship was talking to soldiers and reading about behavior in war,” (italics inserted). He added, after reaching out to Grossman, “from the Colonel…in the days when his books were created, there was very little by way of review.”

This is patently false. Anyone in 1995, 2021, or 1947 could submit their work to a peer-reviewed journal or academic society for peer review. The IRB process has been a component of behavioral science before, during, and after Grossman’s “research,” and would have evaluated and held Grossman to a rigorous set of academic and ethical standards. University of Texas, Arkansas State University, and West Point, large institutions that require students and professors to undergo IRB when conducting research during their program or as supported faculty, could not provide any records indicating that Grossman consulted with IRB, let alone underwent a peer review or ethical review process. Grossman’s evasion of peer review allowed him to directly inject fabricated data and theories into military, police, and mainstream culture, a pattern that seems further replicated by would-be or “natural successors” to Grossman and On Killing. A prime example of the problematic proliferation of Grossman’s flawed theory is the recently published “On Killing Remotely” by former UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicle) squadron commander, Wayne Phelps, who builds his work directly and deliberately on Grossman’s framework for understanding killing behavior and its significance for society. While Phelps, like Grossman, introduces important questions regarding the impact of killing within the more specific realm of UAV operators (or RPAs, remotely piloted aircraft armed with surveillance and missiles for the purposes of targeted or “precision" killings) during the United States’ global war on terror campaign, he repeats the same error as Grossman and their mutual predecessor SLA Marshall by basing his assertions on very limited data and perhaps failing to account for bias within his study. Lived experience, as this author knows, is key in understanding the needs and behaviors of service members; however, not at the expense unsupportable conclusions designed to fulfill a social agenda, such as presenting military service members in a preferred light.

Essentially, if Grossman were to take his work in front of a panel of reputable scholars, it would not pass muster. Lessons preventing unethical research, skewed data and analysis, interjection of personal and cultural values within conclusions, and the many other errors littered throughout On Killing are commonly taught at the undergraduate level. But again, Grossman’s work remains popular and is cited in scholarly sources, the most notable of which is his piece “Aggression and Violence,” in the Oxford Companion to American Military History (2000), which, like the titles “psychologist” and “Army Ranger,” is referenced constantly as a symbol of authority on the topic of violence. Oxford University Press and several individuals involved in the editing process for that volume were unable to answer questions regarding the quality of Grossman’s research and writing; specifically, the lack of evidence that Grossman conducted interviews, went unaddressed; and nobody knew who selected Dave Grossman to provide the entry, or perhaps, no one wants the credit. What is further confusing is the fact that the editor in chief, John Chambers, authored an article after publishing Grossman’s entry that undercut the value of S.L.A. Marshall, whose work Grossman bases his conclusions on. In an email response, OUP stated that they could not predict:

In the mid-1990s… the controversial figure he has recently become…Grossman's subsequent career as a commentator, consultant, and especially and most recently, as a civilian police trainer, as explained in the press, is indeed troubling. His self-representation as a highly-credentialed expert for this is dubious. However, at the time of the Companion's compilation and publication, he did not suggest the use or application of what he now calls “Killology” studies to civilian police forces. His recent marketing of himself and his project advertising “warrior training,” and “bullet proof warriors,” at a time of increasing concern about the “militarization” of local cops were, in the mid-1990s, decades in the future. In the last half of the 1990s, his future trajectory could not be forecast two decades in advance. (Italics inserted)

The individuals providing commentary were not holding positions at OUP at the time Grossman was selected to provide an entry in the anthology. Current staff and former editors unanimously recognized the destructiveness of Grossman’s views and activities over the past two decades, offering the possibility “that a caveat may need to be inserted on the online version of Grossman’s entry”. OUP staff wrote, “This is a very significant issue, and we on the editorial board and at Oxford University Press, are continuing to study the matter very carefully before making a decision.” No “caveat” has been published to date. The publication of fabricated or poorly researched materials is reminiscent of the infamous peer review “hoax” in which three scholars successfully placed peer-reviewed articles in significant academic journals, displaying the fallibility of academic publishers. The difference between the fake articles submitted and accepted in this experiment, and Grossman’s work, is that while the fake articles include flagrantly silly and counter-argumentative language, Grossman’s work misleads policymakers and communities as they attempt to reduce and react to violence.

Highlighting the hubris of displaying an encyclopedic entry as a universal endorsement from academia is not meant to damn scholars who cite or read Grossman (many do so to simply explore the literature on topics like killing, war, and views originating from current and former military experts, not to align with or support his views or theories) or organizations who, like Oxford, invited him into their midst without proper forethought as to the ramifications of promoting his views. Many people possess a curiosity towards violence and should not be faulted for attempting to understand behavior, seek information, or share knowledge. The factors involved in Grossman’s ability to gain a reputation amongst various communities and research and policy institutions, however, represent a series of points of failure which deserve study in and of themselves. Through popular messaging, clever marketing, exhibiting a ‘warrior-scholar identity,’ a charismatic and persuasive personality, and either cunning exploitation or sheer luck of rising to prominence when ‘us vs them’ exploded as a marketing tactic, Grossman holds a dangerous spark to the powder keg of American culture wars.

Popularity of “Killology”: Why Drink the Kool-Aid?

If Grossman’s research is so erroneous, why are his works so popular amongst military and law enforcement? After all, On Killing has an Amazon rating of 4.7 of 5 stars with nearly 2300 reviews, has amassed 3200 citations on Google Scholar, and is commonly cited in multiple papers and books on violence, war, killing, crime, and social contexts of killing. Grossman’s message reaches broad audiences, from The University of California-Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center Magazine, to thousands of Marines after its inclusion on the Commandant of the Marine Corps’ professional reading list. Grossman points to broad demand as the “acid test” for the validity of his theories and research — if it’s popular (or on the internet), it must be true. But broad demand support does not equal validity; it simply proves that aspects of his conclusions and theories appeal to different types of political or ideological beliefs. Berkeley and the Marines are attracted to Grossman’s work because certain properties of killology support each groups’ agenda. Believing humans are instinctively reluctant to kill fits an idealist, anti-war narrative. And Marines want to know more about the process of killing so they can more effectively, well, [fill in blank]. Even academic disciplines and institutions may cheer on the expansion or utilization of faulty claims if it increases the spotlight (and funding) for that discipline. Popular adoption of scientific claims (or claims of scientificness) does not automatically equal scholarly value or harmless consequences — only that a group may manipulate a theory or use specific conclusions to validate established beliefs and objectives. (As any dedicated social scientist or historian will know, there is no such thing as values free research and writing).

Human history is filled with genocidal or oppressive periods, where perpetrators consistently believed their actions were justified by “evidence” or reasoning, and contemporary theories presented by “thinkers” or leaders reinforced assumptions of justifiable killing. (Also ironically, Grossman discusses this caveat in detail in On Killing, which can be accurately applied to his own pattern of behavior and that of individuals and groups who ascribe to his teachings). Unfortunately, the rise of historical patterns of demagoguery and pseudoscience often go unchallenged by elitist scholars occupying the ‘Ivory Tower’ of academia. For their part, military and police communities often seek answers or research results that fall in line with existing objectives and worldviews. This dysfunctional cycle reinforces confirmation bias amongst leaders, policymakers, rank and file, and organizations and communities, leading to destructive social movements. Additionally, Grossman and followers developed an ingenious pattern of independently publishing, bypassing academic scrutiny while maximizing direct contact with consumers. Combined, such factors permit the flow of pseudoscientific works and ‘bad intel’ on policy and practice.

Sheepdog Legacy and Culture: Taking on a Life of Its Own

The ‘sheepdog’ analogy impacts the military and police communities’ understanding of violence more than any other component of Grossman’s work. It is a complex mechanism touching on racial stereotyping and othering through powerful language, metaphor, rhetoric, religious beliefs, and justifications of violence through symbolic representations of ‘good’ and ‘bad.’ Citing John DiIulio, inventor of the term “superpredator” and academic caught up in law and order politics of the 90s, Grossman directly links sheepdog to the destructive racial moniker.

A New York Times article describes the result of DiIulio’s use of the “superpredator” as a term used to describe young men of color who commit violent crimes: “Although [he was] a respected academic, [he] was suddenly questioned by peers, who said he seemed to be providing cover for what they considered partisan politics.” In a literal ‘come to Jesus’ moment, DiIulio realized he had been“misdirected, and I knew that for the rest of my life I would work on prevention…” DiIulio “tried…to put the brakes on the superpredator theory, which had all but taken on a life of its own…Soon, what had been his chief theory was discredited: instead of rising, the rate of juvenile crime dropped by more than half.” According to colleagues, “‘His prediction wasn't just wrong, it was exactly the opposite…his theories on superpredators were utter madness.” DiIulio lamented his involvement in promoting the fear-based, politically motivated term, stating that, “If I knew then what I know now, I would have shouted for prevention of crimes.”

Grossman’s Sheepdog, which he claims in On Killing originated with an “old retired colonel” and “Vietnam veteran,” is drawn from fundamentalist interpretations of Christian philosophy and morality regarding the act of killing. The Sheepdog is authorized to enforce the will of the great shepherd using “righteous violence.” This view contradicts many Christian philosophical approaches to violence and war. That Grossman uses his seminars and writing as a platform for evangelization is painfully evident in the culmination of a 2015 Bulletproof Mind seminar, when, after encouraging an audience of U.S. military personnel to get their hands on a Bible, Grossman re-translates biblical texts to persuade service members, without citing any studies in just one of many examples of numerical hyperbole, that “99% of the religious community for the last 5,000 years believed the proper translation [of the commandment thou shalt not kill] was ‘we shall not murder.” What Grossman fails to expound upon or perhaps understand is that, historically, the difference between murdering and killing rarely depended on clearly objectionable actions of would-be targets, but the perception of that person, group, or people as a threat or demonized other – Grossman’s “Wolf.” This blatant disseminates of crusader language may as well be rephrased: “To Kill an Infidel is Not Murder; it is the Path to Heaven.”

Grossman further links “Sheep” to popular beliefs surrounding the Vietnam War. Specifically, that Vietnam was lost due to a lack of political and social support for the military, and that the rise of post-traumatic stress disorder, addiction, and suicide amongst veterans resulted from ‘hippie’ protesters spitting on returning service members, a myth debunked by Vietnam Veteran and Sociologist Jerry Lembke in Spitting Image. While there were (and still are) undoubtedly cases of disrespect for men and women in uniform, according to Christian Appy in “Working Class War,” Vietnam War protesters were just as or more likely to aid and support servicemembers seeking help, many of whom were draftees from the lowest rungs of the socioeconomic ladder.

Grossman argues that virtue, discipline, masculinity, and warrior ethos – key aspects of the “good guy with a gun” – are being crippled by a radical-leftist society, leaving individuals and communities defenseless. Any other interpretation is flawed and runs counter to the ideals of American exceptionalism. Against this backdrop, Sheepdog provides a framework to organize the self and others into convenient archetypes — scapegoat (sheep), hero (sheepdog), and villain (wolf). Each of these archetypes are steeped in biological determinism. Lawrence Lengbeyer, a professor in the Department of Leadership, Ethics, and Law at the United States Naval Academy, summarizes the danger of Grossman’s rhetoric and the Sheep-Sheepdog-Wolf (SSW) metaphor to our military community:

Rhetoric matters. It has potent psychological effects, and sometimes potent political ones, too. It is capable of shaping personal identity, in turn shaping emotion, cognition, and behavior. Military personnel who are encouraged to view themselves as ‘sheepdogs’ protecting ordinary-citizen ‘sheep’ from predator ‘wolves’ are liable to develop a dangerously false sense of moral superiority, to chafe under civilian control, and to prize aggression above more important intellectual and moral virtues. They could be induced to under-value democratic processes, constraints, and freedoms, focusing single-mindedly upon physical security rather than upon safeguarding civil liberties and the American Constitutional system, tasks for which their supposed ‘gift of aggression’ is rarely an asset. The pernicious attitudes fed by the SSW are not dependent upon its specific terminology; they can certainly be promoted without it. And civic cultures can be poisoned in comparable ways with the help of other ideological and linguistic instruments.

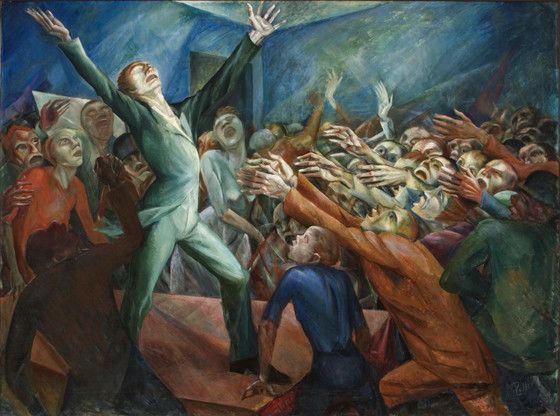

Returning to the role of “Hollywood” and media further highlights how embodying the Sheepdog analogy can be harmful to a service member's or police officer’s psyche. Think John Wayne, a looming figure in masculine-paramilitary culture, and the final iconic scene of one of his most well-known films, The Searchers. The Duke’s character, returning from the harrowing rescue of his niece from marauding, savage Indians, lingers outside the threshold of the family home. After reflecting on his place around the family hearth and within society, the seasoned warrior saunters into the desert, turning away from the happy reunion. This scenery perfectly captures Grossman’s Sheepdog identity, and the potential harm caused when a police officer or servicemember incorporates and reenacts a symbolic representation of what is perceived as proper masculine culture within his or her own life experience. The Sheepdog, willing and able to use righteous violence, cannot fully rejoin society due to his experience and choice to accept the mantle of responsibility and burden of protecting the sheep.

Grossman argues that society must be willing to accept and support, without reservation, Sheepdogs as living martyrs who keep the wolves (People of Color, the Mentally Ill) at bay. These claims engender dangerous attitudes with respect to deadly use of force, overemphasize the role of shootings within police and military life, further instilling a fear-based world view. The result is immeasurable psychological harm to individuals who feel socially obligated to subscribe to the ‘doomed soldier’ script and are left unequipped as individuals and members of larger organizations to resolve and heal from mental health challenges such as depression and anxiety, often resulting in suicide. We must also ask, what happens to the service member or police officer who does not fall in line with the cultural consensus on killing, as prescribed by the sheepdog analogy? Could police and service members feel a sense of shaming, anxiety, or moral injury by refusing the tenets of killology or “warrior mindset” during their career? Will police officers and service members, realizing that the sheepdog analogy naturally leads to othering and fear-based approaches to fulfilling one’s duty, and as a result, increased aggression and hostility, feel a sense of moral injury at enduring in a toxic culture or participating in an act that transgresses their own set of values and ideals?

The logic involved in Grossman’s campaign against violent video games is also applied to Western films, by portraying this classic genre as a source of the moral storyline. Compared to video games and their faceless virtual enemy, Westerns allow viewers to recognize and distinguish between authorized and unauthorized targets by displaying killers and those killed as racially, nationally, ethnically, or otherwise distinct and different. If one reads deeper, the issue is not so much that youth or adults are exposed to imagery of killing and violence, so much as they are not exposed to imagery that reinforces an ideologically and socially acceptable target.

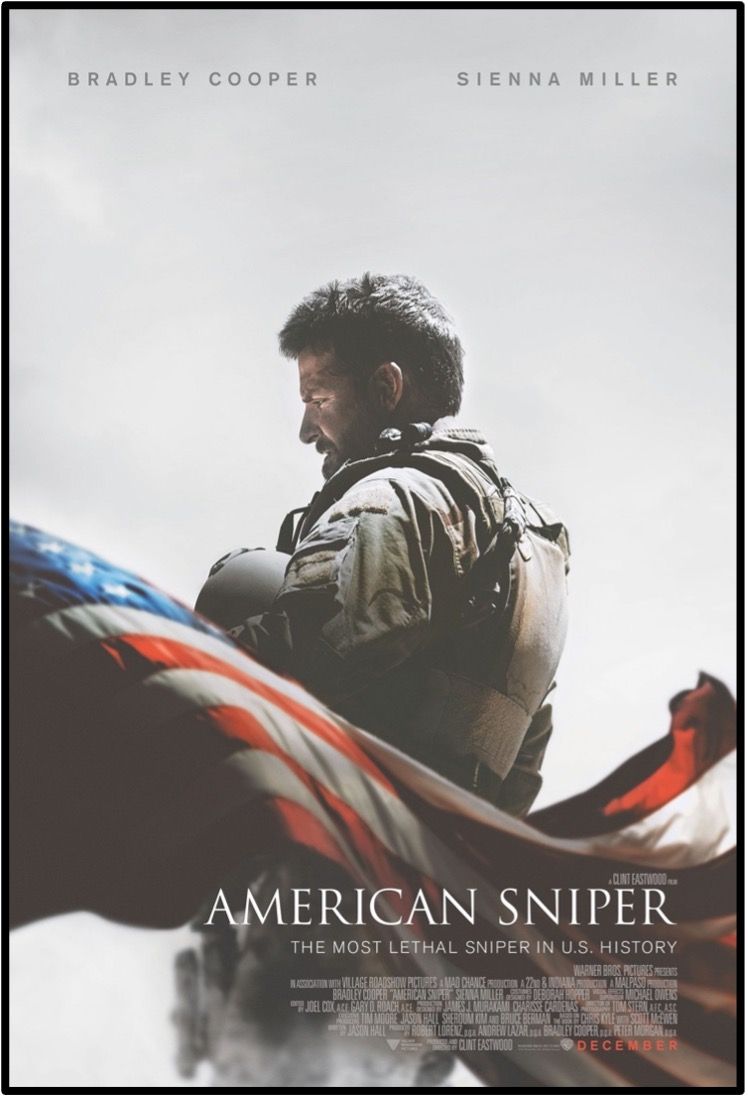

Many leaders in law enforcement and police organizations, however, push back against the “warrior mindset,” instead advocating for a “Guardian” approach. But Sheepdog is entrenched and fetishized within military, policing, and paramilitary communities, particularly throughout popular culture, and is embedded in Hollywood are portrayals of the anti-hero or “good guy with a gun” (e.g: James Bond, Dirty Harry, the Punisher, American Sniper).

Sheepdog is the identity de jour for private and publicly funded tactical training, security services, and law enforcement, security, and home defense expos. and the powerful branding of Sheepdog through clothing, merchandise, iconic imagery, patches, texts, and even tattoos parallels movements that share in its ideological base, like the thin blue line and many conservative politics factions.

The deep-rooted nature of the “Sheepdog” subculture within law enforcement, supported by pseudoscientific knowledge and spearheaded by Grossman, makes the difficult task of improving community policing nearly impossible. As one national expert on policing put it, “culture eats policy any day of the week.” New and revised policies and practices intended to improve community policing, counter violent crime, and address systemic issues will ultimately fail to reach their full potential due to cultural beliefs and patterns of behavior existing within law enforcement. None of this is to say that violent crime is not a pressing issue, that law enforcement does not need support and training in escalation, de-escalation, and use of force, or that both law enforcement and military personnel need to be equipped to handle the effects of combat — it is and they do. But the research behind training, policy, and practice must be grounded in the best standards of scholarly research.

However, pursuing more nuanced and productive research on community policing requires more active involvement of collaborative researchers who focus on the topics of culture, society, and organizational behavior. While many, including myself, are more than willing to participate in research with and for policing organizations (despite the seeming criticisms of police by proxy of criticizing a cultural figure), there are many within academia who, due to their own ideological beliefs, either choose or even protest the involvement of behavioral studies of policing behavior that center on the experiences, beliefs, and motivations of police officers. Essentially, the fear or belief that to understand a police officer is to justify the socially unacceptable behavior that some police officers commit and have committed as members of a larger system of oppression, prevents the application and involvement of potentially lifesaving and culturally grounded research by those who are particularly skilled and trained to conduct that research.

The choice to withdraw from a complete examination of American policing is fueled by the same sense of loyalty to ideological and cultural beliefs that is present in communities that protest police brutality, especially amongst racially marginalized communities. This point was made strongly in conversation with leadership in the Michigan Police Chiefs Association, who offered, publicly, after the cancellation of Dave Grossman’s bulletproof mind training in Ann Arbor, to facilitate a conversation between Grossman and his supporters, and community members and protestors. This balanced and just call for a meeting to facilitate understanding and dialogue between members of the policing community and, more specifically, the Black Lives Matter movement, received no response. The fact that many members of what are viewed and described as oppressed and oppressor communities often do not meet to reconcile and recognize grievances, or that such reconciliation seems to be the exception rather than the norm, represents an additional failing amongst 20th and 21st century academics, who historically ally themselves with the “subaltern” or communities relegated to a lower rank, to the detriment of understanding systemic violence.

To understand the experiences of the oppressed, we need to hear, uplift, and primarily, give ground to the oppressed to speak for, with, and to themselves and to wider communities. To understand systems of oppression and violence, however, we must understand the motives, drives, and behaviors of those we perceive as belonging to both the oppressed and oppressor groups, which ultimately dictate how each participate, benefit from, and are harmed by such systems.

Addressing Grossman’s Defense

In June 2020, Grossman posted on LinkedIn his apparent “response to recent “journalist” attacks and inquiries about” his work. In his post, Grossman required that media coverage of his work: 1) acknowledge that he is an “Author” 2) report on a full assessment of his work, 3) acknowledge his contributions have a documented impact on many communities, such as the emergency medicine community, policing community, etc… 4) acknowledge his books and writings have been established in their respective fields, and he 5) challenged anyone criticizing his work to ask themselves: “…are you a “journalist” as you claim to be[?] Are you a professional who will inform the reader about my books, in case they should desire to get more info, and give an accurate representation of my work; or are you engaged in intentional, malignant character assassination, concealing critical information from your readers?”

Indeed Grossman 1) is an author, 2) his materials have been read, listened to, and viewed in the context of their conception and delivery, 3) his contributions do and likely will continue to impact a great many people and communities, 4) and his books and writings have been established in your own field of Killology. Number five is difficult, however. I am not a journalist. I am a Marine infantry veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom, public health professional and advocate, and anthropologist using a journalistic platform to discuss the pseudoscientific roots of Killology and the harmful impact of your work.

How, and Perhaps Why, Did We Get Here?

Whether Dave Grossman saw On Killing, Killology, and Sheepdog as opportunities to satisfy the ego, gain fame and fortune, promote a personal sense of right and wrong, inject his own cultural and religious beliefs, or some combination of these or other motives, is open to interpretation. Regarding ‘fortune,’ with a $6,000 (plus travel and expenses) minimum for lectures and thousands of appearances, a handsome reward for his writings, online classes, and merchandise sales, even a conservative estimate would place Grossman in the multi-millionaire range. Profiteering from fear and junk science is a problematic issue for military and law enforcement that extends beyond Grossman. A Warrior-Scholar trend (or movement) continues to grow in our military, law enforcement, security, and martial arts communities, where individuals with one or more of these backgrounds write, speak, and profess revolutionary insights on combat, while displaying varying degrees of experience, academic training, and critical thinking ability, or recognition of their own biases and motivations. While there are many benefits of representing lived experience within military and police training, policy, and practice, there is a danger that lived experience is being hijacked by individuals who use it as a vehicle, knowingly or unknowingly, to fulfill personal or social agendas.

The purpose of this article was not simply to kick up dust, but to remind readers that the first step in solving any problem is realizing that you have one. While other works have addressed Grossman’s influence and foundations for the “Sheepdog” paradigm from different angles and styles, Grossman is rarely criticized within a venue that speaks directly to a larger audience of military and law enforcement, and from the perspective of a member of the veteran community with backgrounds in fields in which Grossman claims to be an expert. Regardless of personal beliefs, we must agree that research and messaging surrounding topics of violence must be grounded in critical thinking skills, empirical evidence, and scientific rigor and that an honest ‘gut check’ is needed regarding our biases and motivations for pushing certain views on killing and violence. We do not need assumptions, false claims, or pseudoscientists using violence as an opportunity to fulfill a messianic role, no matter how good their words make us feel or how conveniently certain claims justify mentality and behavior. Or perhaps we should view words and language with suspicion specifically because they make us feel good and provide convenient justification. Finding the truth about killing, war, and combat is an admirable endeavor, but Dave Grossman has proven he’s not up to the task. And worse, if the recent events in Uvalde, where police officers, many of them surely loyal to the “sheepdog” identity, and dozens of school shootings in recent years are any indication, Grossman’s successful efforts to push the hyper-militarization of American police pushed us away from the critical work of reducing gun violence in America and barring many from moving through the door to save lives.

Postscript: Uvalde – Where Have All the Sheepdogs Gone?

Rather than shuffle the recent tragedy at Uvalde, which took place during writing, into the existing version of this article, I believe that the children and teachers lost, the grieving community, and the specific contexts surrounding the shooting at Uvalde deserve specific and separate attention as they relate to the topic of this article. The (in)actions of police in the hallways of Robb Elementary are a poignant example of the real-world harm caused by the Sheepdog identity, which is built around ego, bravado and fanciful beliefs masquerading as courage and tactical expertise and ability. We see with painful clarity that simplistic, and one size fits all solutions are motivated by political agendas and ideology, rather than a genuine mission to understand violence and prevent disaster.

Police officers, many undoubtedly subscribing to the Sheepdog script – according to his CV, Texas is a particularly active recipient of Grossman’s teachings – stood outside the school and classroom while children were being shot to death, bled out, hid in terror, and in one extremely disturbing instance, covered herself in the blood of her classmate and friend and played dead to avoid the shooter’s attention. Students called 911 repeatedly, begging for the police, only to be told they are “on the scene.” When an officer called out to the students if they needed aid, a little girl responded with pleas for help and was immediately gunned down. Still, no one engaged the shooter. Where have all the “Sheepdogs” gone?

At Uvalde, Murphy’s law was in full effect – everything that could go wrong, did go wrong, despite having many tools and policies that were in place at Robb Elementary and the wider school district and recent training and preparation for mass shooting. Alone, no amount of training, deployment of apps (which were present, used, and ineffective at Uvalde), technology, school resource officers, or set of gun laws or mental health bills will stem the tide of violence that we often see displayed through the media. Complex problems require holistic and systemic solutions, and we continue to see the real harm and destruction that results from naïve and unqualified claims as to how we can stop the carnage.

We must ask: have our police officers simply put on the body armor, weapons, gear, and identity of the Sheepdog in order to reinforce or take upon themselves the vaunted image of a hero archetype that aligns with the ideology purported by Grossman? An ideology of good vs evil drawn along political, religious, and nationalist lines? Or do they intend to serve communities and save lives? We must ask how much policy, procedure, practice, and mentality of those responsible for responding to violence and killing, in both military and policing circles, are informed by sources and individuals that either support a cultural or ideological belief system or provide a critical understanding of violence and killing in society?

In one revealing study published in the Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, deadly use of force training stresses the need to win in a deadly force scenario. What “winning” entails, however, may not be related to protecting the lives, (that of the victim or potential perpetrator of a crime). Rather, the social and emotional result of winning is attached to fulfilling the hero archetype. In truth, a police officer in today’s Sheepdog paramilitary culture, due to Grossman’s form of enculturation, may not be mentally equipped to experience failure, even honest failure, not because of the resultant cost to innocent lives, but because it does not fit within the mental schema of the Sheepdog, who is always righteous, and therefore always victorious. I think it’s time that we told that truth to the grieving families and children’s tombstones in Uvalde and around the country.

Sources

Note: These sources are provided as examples of media, journalistic, and academic works that support or expand upon points made throughout this article. However, this is not an exhaustive list of scholarly sources which have been collected in the process of independent research on the topic of Dave Grossman and the role of Sheepdog and Killology within policing discourse in America (Allard, accepted for publication). For additional sources or bibliography, please contact the author.

Education Week. “School Shootings This Year: How Many and Where” Education Week’s 2022 School Shooting Tracker. January 05, 2022 (Updated: September 02, 2022) https://www.edweek.org/leadership/school-shootings-this-year-how-many-and-where/2022/01

Code for Couples: Heroes Don’t Do it Alone. “Sheepdog Mentality Featuring Lt. Col. Dave Grossman” October 21 st , 2020. https://www.code4couples.com/podcasts/sheepdog

Kelly McLaughlin. “A police trainer's event was canceled after video resurfaced of him telling cops that killing people can lead to great sex.” Insider. Apr 28, 2021.

“Dave Grossman: Bulletproof Mind” Cannon Airforce Base September 24 th , 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8RDCtMEHFLM

Josh Eells. “Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, the “Killologist” Training America’s Cops” Mens Journal. Februrary 8, 2017.

Bryan Schatz ““Are You Prepared to Kill Somebody?” A Day With One of America’s Most Popular Police Trainers: The dark vision of “killology” expert Dave Grossman.” Mother Jones. March/April, 2017.

Dave Dickerson. “Michigan Association of Chiefs of Police cancels training over controversial speaker” The Detroit News. April 27, 2021.

Grossman Academy. https://www.grossmanacademy.com/

Emily Matson. “World-Renowned School Safety Expert Speaks in Union City” Erie News Now. February 18, 2019

Grossman On Truth https://grossmanontruth.com/

APA Task Force on Violent Media. (2015). Technical report on the review of the violent video game literature. Retrieved from http://www.apa.or g/pi/families/violent-media.asp Accessed 2022

Suziedelyte, A. (2021). Is it only a game? Video games and violence. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 188, pp. 105-125.

Cleared Hot Podcast. “Episode 124 - Lt. Col Dave Grossman”

Buckeye Firearms Association. “Bulletproof your mind with Col. Dave Grossman!” Monday, February 21, 2022.

The Bullet Proof Mind, Course Objectives. Shenandoah University. 2014.

“The Dave Grossman Debate” (Debate Between Dave Grossman and Tom Aveni). The Police Policy Studies Council. Dateline: August 11, 2001.

Gary Quesenberry. Spotting Danger Before It Spots You: Build situational awareness to stay safe. YMAA Publication Center. 2020.

Dave Grossman. American Sheepdogs: Why Mommy Carries a Gun. Killology Research Group. 2018

Dave Grossman “Angel of the Night” War Poetry, Live Journal. 2010.

Bill Coberly. “The Warrior-Cop Ethos and the Stand-Around Cops in Uvalde.” The Bulwark. August, 2022

Crews, G. A., Crews, A. D., & Burton, C. E. (2013). “The only thing that stops a guy with a bad policy is aguy with a good policy: An examination of the NRA's "national school shield" proposal.” American Journal of Criminal Justice: 38(2), 183-199.

Kelly Mclaughlin. “One of America's most popular police trainers is teaching officers how to kill.” Insider, June 2020.

Jennifer Bjorhus “Officer who shot Castile attended 'Bulletproof Warrior' training” Star Tribute, July, 2016.

Niraj Warikoo “'Killology' speaker defends views after talk to metro Detroit police chiefs is canceled” Detroit Free Press. May, 2021

Rocky 'Apollo' Jedick “Combat Stress Response & Tactical Breathing” Go Flight Med. May, 2014.

Counselor Education. University of Texas at Austin. Accessed 2022.

James Clark “The Army can’t officially say who is an ‘Army Ranger’” Task and Purpose. February, 2021.

Kirkus Reviews “On Killing” 1995.

Elliot Cohen “On Killing” Review. Foreign Affairs. March/April 1996.

Robert Engen. (2008) “KILLING FOR THEIR COUNTRY: A NEW LOOK AT “KILLOLOGY”” (Book Review Essay) Canadian Military Journal Vol. 9, No. 2

Lamy, P. (1992). Millennialism in the Mass Media: The Case of “Soldier of Fortune” Magazine. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 31(4), 408–424.

The War Chronicle. Marshalls Ratio of Fire.

Spiller, Roger. “S.L.A. Marshall and the Ratio of Fire” RUSI Journal Winter 1988.

Chambers, J.W. (2003). “S. L. A. Marshall’s Men Against Fire: New Evidence Regarding Fire Ratios.” The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters.

Fonseca, L. M., & Testoni, I. (2012). “The Emergence of Thanatology and Current Practice in Death Education.” OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 64(2), 157–169.

John Boyd Online: The John Boyd Homepage...your source for all things Boyd. Accessed 2022.

Jewish Institute for National Security of America (JINSA) Podcast. “John Boyd: The Most Important American Strategist You Never Heard Of” June 9, 2020.

Lt. Col. Dave Grossman’s Post [Regarding Mass Killers, 2 nd Edition] LinkedIn. 2021.

The Oxford Companion to American Military History. Ed. Whiteclay Chambers, John: Oxford University Press, Oxford Reference. Date Accessed 7 Sep. 2022

Yasha Mounk “What an Audacious Hoax Reveals About Academia” The Atlantic. October 5, 2018

Dave Grossman. “Hope on the Battlefield” Greater Good Magazine. June 1, 2007.

Becker, Elizabeth. "As Ex-Theorist on Young 'Superpredators,' Bush Aide has Regrets." New York Times, Late Edition (East Coast) ed., Feb 09 2001.

Kingdom of Heaven. Twentieth Century Films. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0320661/

Lembcke J. (1998). The spitting image: myth memory and the legacy of Vietnam. New York University Press.

Appy C. G. (1993). Working-class war : American combat soldiers and Vietnam. University of North Carolina Press.

Relevant Radio. In Podcasts, Trending with Timmerie “Thriving, Loving, Finding Joy, and Peace” by Timmerie Geagea. April 12, 2021.

Kimberly Kindy, Julie Tate, Jennifer Jenkins and Ted Mellnik “Fatal police shootings of mentally ill people are 39 percent more likely to take place in small and midsized areas” Washington Post. October 17, 2020

Cristal Hayes 'Silence can be deadly': 46 officers were fatally shot last year. More than triple that — 140 — committed suicide.” USA Today. April 12, 2018

Seth Stoughton “Law Enforcement’s “Warrior” Problem” Harvard Law Review Forum. April 10, 2015.

Konstantinos Papazoglou, Ph.D., George Bonanno, Ph.D., Daniel Blumberg, Ph.D., and Tracie Keesee, Ph.D. “Moral Injury in Police Work” Law Enforcement Bulletin. September 10, 2019

Val Van Brocklin “Warriors vs. Guardians: A seismic shift in policing or just semantics?” Police1. May 7, 2019

Eric Italiano “‘No Time To Die’ Director On Whether The World Needs “Bad Men” Like James Bond (Exclusive)” BroBible. October 5, 2021.

Michael Cummings and Eric Cummings “The Surprising History of American Sniper’s “Wolves, Sheep, and Sheepdogs” Speech” Slate. Jan 21, 2015.

Sheepdog Response. Sheepdogresponse.com Accessed 2021.

Sheepdog Patrol. Thesheepdog.us Accessed 2021

“Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, U.S. Army (Ret.) to Keynote Officer World Expo” Businesswire. April 18, 2012

Trone Dowd. “Cop Seen Attending Proud Boy Rally Sure Dresses Like a Proud Boy” Vice News. March 15, 2021.

Jack Jenkins. “Being a good guy with a gun is what God wants, say ‘sheepdog’ evangelicals” ReligionNews.com September 15, 2020.

Dave Grossman. “Lt.Col. Dave Grossman's Rebuttal to Media Attacks” LinkedIn June 15, 2020.

Mike Baker and Dana Goldstein “Uvalde Had Prepared for School Shootings. It Did Not Stop the Rampage.” The New York Times. May 26, 2022

Aaron Katersky and Meredith Deliso “Security app sheds more light on emergency response in Uvalde school shooting” ABC News. June 3, 2022.

Broome, Rodger. “An Empathetic Psychological Perspective of Police Deadly Force Training” Journal of Phenomenological Psychology 42 (2011) 137–156.

![[Guest Post] Exploring Colonial History through Art](/content/images/size/w750/2023/11/graphite-island-banner.png)