To be Weak, Sick, and Laugh: Notes from the Field

A large plaque at the center of an office in Urakawa, Hokkaidō (northernmost island of Japan) writes:

Do not work hard 頑張らない

The office is used by a group called Bethel House ('Bethel' from here), originally a peer-support group for those who received a psychiatric diagnosis in the 1980s. Today, Bethel has expanded into a complex organization involved with the local production of kelp and strawberries. Bethel also regularly publishes widely about their work, which has now gained a worldwide following.

Through the invitation of one of the founders of the organization, Mukaiyachi Ikuyoshi, I spent a few days in Urakawa experiencing the unique method of "tōjisha kenkyū" myself.

What is tōjisha kenkyū?

As recently written by Dr's Ayaya Satsuki and Kitanaka Junko, "the word ‘tōjisha’ is difficult to translate accurately into English" (Source). Originally used to refer to parties involved in a litigation, its use has expanded to be used by people who identify as a social outsider. Within Dr. Nakamura Karen's analysis of Bethel, tōjisha is described as such:

In Japanese social movements, the term has become a useful gloss to mean all people who have encountered discrimination or members of a discriminated class. But it is also used as a polite way within discriminated communities to indicate membership: 'Are you a tōjisha? Yes, I am a tōjisha.' (Source)

Next, "kenkyū" can simply be translated to "research."

Following this, one of the core ideas of tōjisha kenkyū is to study ones own problems. As Bethel started among tōjisha's with a psychiatric diagnosis, many of these research projects involved exploring their hallucinations, depression, suicidal behavior and thoughts, addiction, and more.

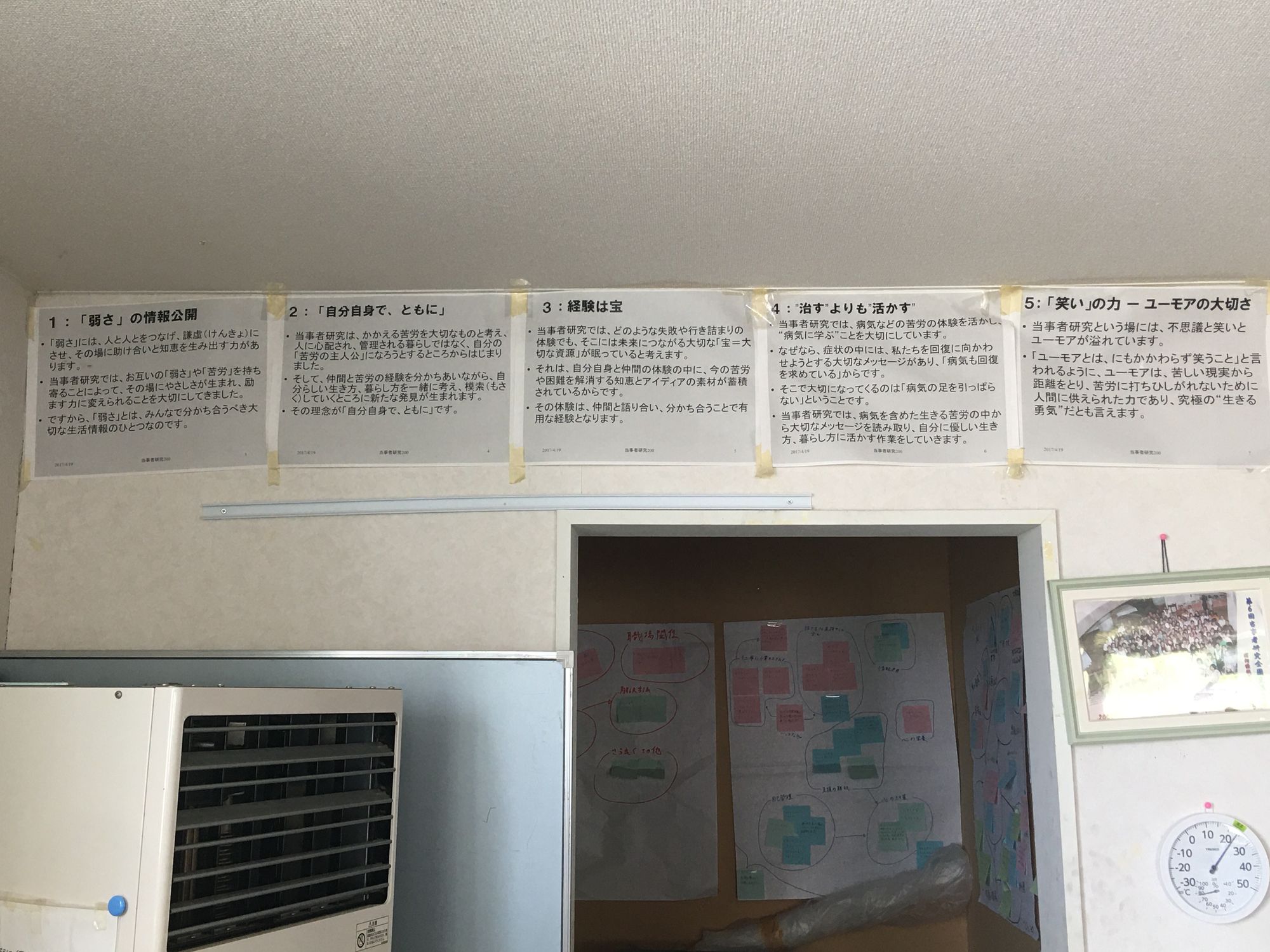

Although there are many principles that Bethel has created – such as "publicly displaying one's weakness" or "the power of laughter and humor" – the one that catches my eye the most is the practice of creating a "self-diagnosis."

Members and visitors of Bethel are encouraged to create a name for their own problems, full of humor and specificity to their own issue. In a series of books created to introduce tōjisha kenkyū, a member introduces her disease as "Look at me Syndrome, Self-harm type."

By naming one's own diagnosis, it allows one to think through their own problems and create a unique expression to share with others.

As such, tōjisha kenkyū highly values expression, intentionally utilizing language and art to alter one's perspective towards their struggle. Bethel does not say "you have a problem" but "you are struggling." Not "you have failed" but "you have experienced." Not "to understand oneself," but to "understand the pattern and meaning of struggle."

Not a person with a struggle, disease, or weakness, but to separate the "person" and the "problem." And importantly, to share this in laughter and humor.

No Manual, but a Framework

Now, if you have made it this far, I imagine that many have one question:

So, how does one do tōjisha kenkyū?

Well, there is no manual. It is totally up to the struggle, the person, their community and environment, and many other aspects (such as, are you hungry? Are you busy? Are you at a place where you can speak and write?).

Instead, there is a general framework, which follows the steps of scientific research. That is:

- Asking a question (Why do I keep thinking about worst case scenarios?)

- Creating a hypothesis (Maybe I am being too aware of what other people think)

- Testing the hypothesis (Survey; Try to live for a week by intentionally being aware of what other people think; To openly tell people about my awareness of others etc).

- Reporting results

- Repeat.

What is key, as Mukaiyachi said over dinner, is "to constantly be curious about oneself." He continued:

Let's try to always have the words, "then, let's try to research that!" in our back pocket.

Conclusion and a Deeper Inquiry

There are many more fascinating aspects of Bethel and tōjisha kenkyū that will take too long to write; I will add links to such sources at the end of this article. All I hope is to provide a taste of curiosity on tōjisha kenkyū, and allow you to take your own journey of being exploring about your problems and this research method (I don't say research method lightly, there is now a tōjisha kenkyū research center at the University of Tokyo, the most prestigious university in Japan).

However, there is a question that has gone unanswered within me as I learn and get involved with Bethel:

Why did such a unique community emerge at the outskirts of Hokkaidō, Japans' first and longest standing colony?

But that is for another time. Enjoy researching and laughing at your weakness, sickness, and tōjisha-ness.

![[Guest Post] Exploring Colonial History through Art](/content/images/size/w750/2023/11/graphite-island-banner.png)

![[Guest Article] On Grossman: How a Pseudoscientist Pushed Our Understanding of Killing Back 20 Years](/content/images/size/w750/2022/09/256297-1330622535.jpeg)