Writing 3,000 Words and Taking a "Break"

I'm taking a break.

Not because I'm tired and worn out from writing these newsletters, but because the topic I've been trying to cover for the past few weeks require more than just a few newsletters. Every draft seemed incomplete, and I did not want to leave any reader in a place of loss.

Therefore, I'm taking a break to focus on this new project.

But before I do so, I wanted to reflect upon this year and share some of the insights I've gained for myself as I try to publish these articles weekly.

Early on this year, as I just started off on this odd journey, I decided I needed to write much more.

So in a rash moment, I decided to write 3,000 words a day minimum. I don't quite recall how I ended up on that number, but very quickly I regretted setting the bar so high.

The problem was that I did not have enough words to fill the page. And this is where I learned of the magic and essence of words and language itself.

No word can't stand alone, it just doesn't make sense for them to be. Words are ontologically relational. They refer to an object, describe it, expand on ideas, and more. Words also relate to each other; they enhance, break down, or even complicate the other words it stands alongside. So to aid this, we have facial expressions, hand gestures, pauses, tone, and more to add to this complexity.

This is the beauty of storytelling. One story is told, then another is added onto it. Words are not just a long thread to be continuously extended, but through the gift of sharing and discussing stories, words gain a new dimension.

One of my favorite studies was done by a large group of scholars in the United States, who looked into how consistent someone's memory is throughout a period of 10 years. Specifically, they looked to see how people remember the tragedy of 9/11 differently throughout time. We would expect a story so impactful to remain as it is, right?

Well, the results are quite shocking.

With minimal variability, everyone – of the 3,000 subjects – lost, reconstructed, or misconstrued their own initial stories 10 years ago. Some even reported denying their own story; saying it was falsified because the handwriting was different. On average, the scholars suggest that about 60% of these stories changed.

60%!

There are many things to learn from this – notably how our memory is not as good as we would all like to believe. But I want you to focus on another part of this study.

The story these people told did not change because they sat alone in their room for 10 years. It most likely changed and developed because they continued to share it, and other people shared theirs with them. The narrative of one of the most significant events of their lives changed because we are relational beings, using relational words.

In 1985, a social psychologist by the name of Daniel Wegner proposed an idea called "transactive memory". Although it wasn't used to necessarily praise the nature of human beings, there is a poetic side to this theory.

Transactive memory is the idea that we store bits and pieces of our own memory, experience, and most importantly, identity in other people. For example, an important part of my childhood is stored not in my own mind, but in my parents and older brother's. In this way, the "hole" many people speak of when they lose a loved one is extremely telling. We literally lose part of ourselves when we lose a loved one.

But why am I telling you all this? I started from the story of how I struggled to write 3,000 words a day right?

It is because these two ideas are fundamental in the way I learned to write.

Just like how words are relational, so are our stories. And even more importantly, the way we tell our stories truly matter. By sharing and exchanging a certain narrative, we can quite literally alter the way others understand their own past and identity. A simple addition to the narrative, like, "No, I think we were in the coffee shop when 9/11 happened!", could lead to much distress for someone who thought they were in their bed when the event occurred.

Now, I must admit that is a rash example, but I believe it gets to the point. So the lesson here is that telling stories – as I've attempted to do through these articles – is a collective dance in constructing different narratives.

But if the words I use step too far away from the words you use, they can't resonate and relate. Even if we are speaking of the same "event", our stories don't interlock and there's nowhere to go. On the other hand, if my words align too closely with yours, then again, it's not getting us anywhere. So then, how do you maintain the balance?

Join the dance.

Soon after starting this project, I learned that for me to tell a story, I first need to make it my own. Not in the sense of private ownership, but in the sense Daniel Wegner thought of memory: I had to make the stories personal.

At first, many of the stories I wanted to write on were dancing away in the distance, as I sat observing comfortably alone. But again, no words can be conjured up alone. You have to get up and ask that story to dance, follow its every step and make it your own. But to just learn one dance is to create an echo chamber of the same narrative. Soon after you learn one dance, you store it neatly inside yourself, then go ask another narrative for their hand.

By doing this you not only increase the various perspectives and narratives of a certain event, but you also quite literally learn their words. A particular adjective from one story may have resonated with you, while a certain noun stood out from another. And by stringing these together, you not only create a new narrative but bring the two different dances together.

So to add to the above idea, it is to dance a lot.

The dance of words nowadays comes in the forms of books, articles, podcasts, videos, movies, and more. But most importantly they come in the forms of conversation. The most formative part of my learning process is to email or call every single author from whom I would like to borrow an idea from. 9 times out of 10, they don't respond. But those 1 or 2 times they have responded and entered a dialogue with me, often alter the very nature of the story I want to tell.

Now you may think that was just a long extended way of saying: "Maximize input to maximize output".

You could not be more wrong.

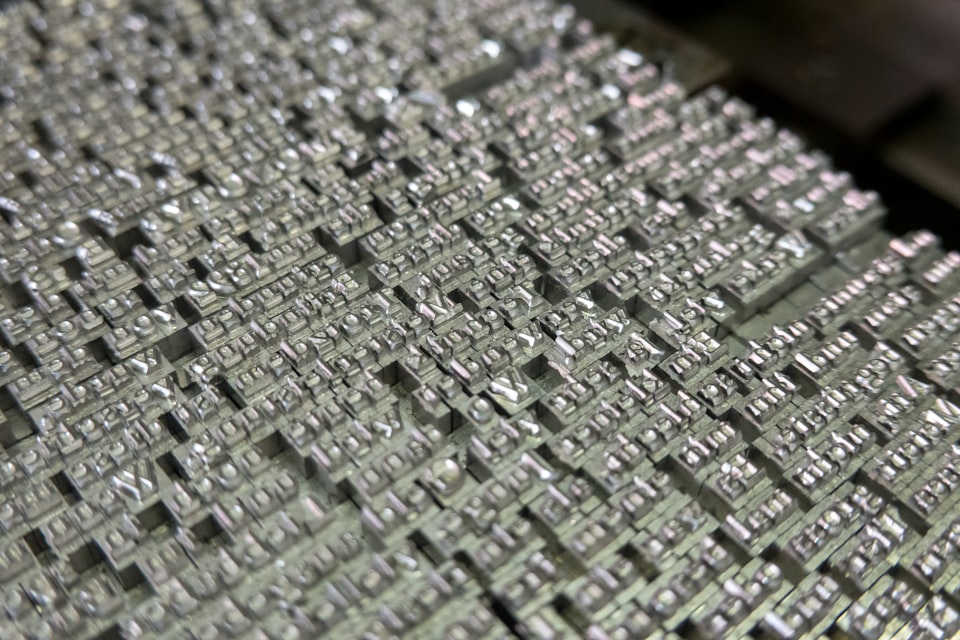

Putting down 3,000 strings of symbolic characters that look like an alphabet is not hard. Just input more characters, then the more characters come out; right?

But writing 3,000 words – that relate not only to each other but to other narratives and stories – is extremely hard.

And that is exactly why I am taking this break. The stories I want to tell are hard and require every ounce of attention.

Stay tuned,

Hosanna

![[Guest Post] Exploring Colonial History through Art](/content/images/size/w750/2023/11/graphite-island-banner.png)